That’s right. Math.

Here’s the deal: If you’re an independent contractor or freelancer (no matter part-time or full-time), you’ve probably had some headaches over irregular income. The good news is that you can improve your budgeting and cash flow management outcomes with a little math rigor. The bad news is that we talk about stuff like expectation-maximization algorithms and multimodal distributions and other things you don’t care about. The bad(der) news is that life is unpredictable, so there’s no guarantee here. But perhaps we can mitigate some uncertainty.

Figure out your rate.

One of the issues that I’ve seen with irregular income budgeting is just where to start. First and foremost, if you haven’t worked through your hourly or per-project rate using market data based on your job title and experience, then stop reading this and figure out what you need to be paid on a self-employed basis to create a salary replacement value. You need to factor in things like the benefits you would otherwise receive as a W-2 employee, your retirement savings, self-employment taxes, overhead, business development time/expense, etc. A common rule-of-thumb is to set a daily rate of pay equal to 1% times your W-2 annual salary… but you owe it to yourself (and your bank account) to do the math here.

From here, we can use historical income data to start creating some probabilities of cash flow. If you’re just starting out (or haven’t made the plunge), you could still run this experiment but use values based on colleagues’ experiences who are in the same field… assuming your rates and earning potential are similar.

The common approaches.

From some research on the internet and talking with independent contractors, we’ve picked up on two common ways to manage variable cash flow and handle budgeting issues. The first is to take the average monthly earnings from your income history (or perhaps just last year) and use that to build your budget around. The second is to take the minimum you were paid over some historical period and budget around that value. The problems that arise are nontrivial:

- Using average earnings will undoubtedly require you to dip into savings more than you’d probably like.

- Using minimum income will force you to perhaps live more frugally than you’d like.

- You still worry about cash flow and budgeting.

For example, let’s say your 2-year monthly income history looks like this:

7200, 7600, 9000, 7300, 2900, 7000, 7100, 7000, 2100, 4300, 8300, 7700, 4800, 3200, 3500, 3000, 3200, 3800, 7200, 7100, 7000, 7500, 3000, 3100

(A caveat: Yes, this is technically a time series that could possibly be decomposed into a seasonal element or trend component, but that’s not the point right now…)

If you were to use the average earnings approach, you would set your budget at $5,579 per month. And guess what? You can see that while the first part of the income series looks healthy, you hit a rough patch at $2,100 and then again at $4,300… and then the train falls off the tracks during the time where monthly income hovers around $3,000. Yikes.

If you were to use the minimum earnings approach, you would set your budget at $2,100 per month. Life is good, except that the belt is probably a little tighter, you’re thriftier, and really good months could tempt you to splurge and forget about saving for long-term goals.

A better approach?

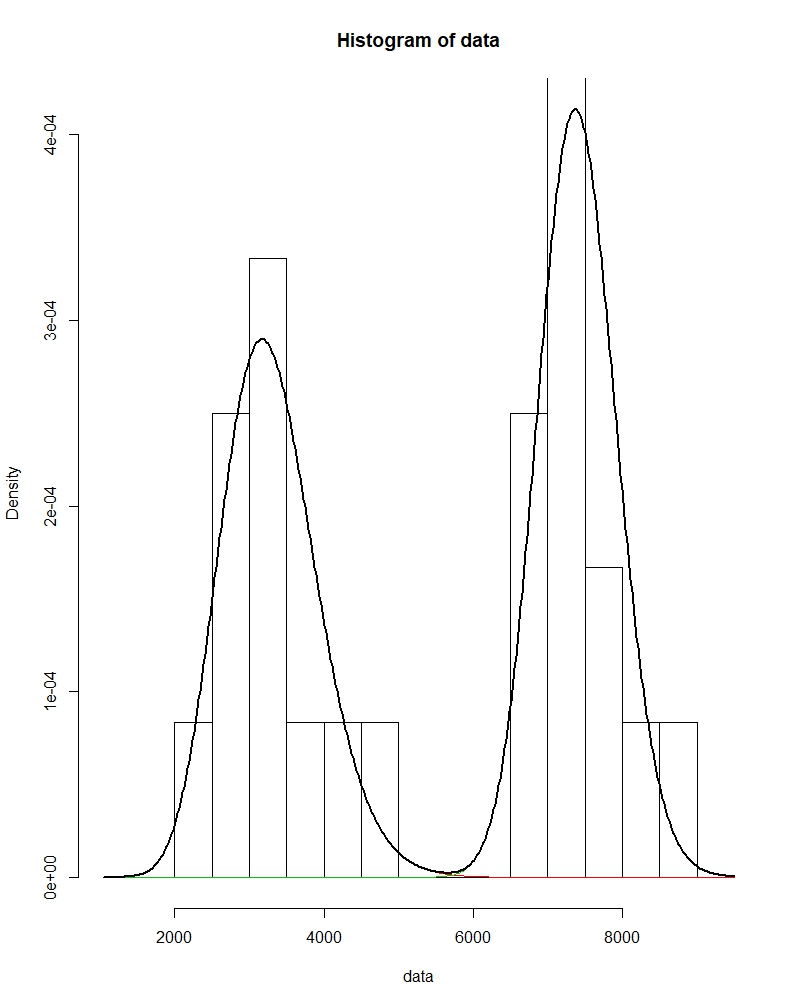

Here’s a histogram of the income history that shows bimodal data… or two peaks in the bars:

So while averaging out your monthly income lands you right between the peaks, you still have to deal with the fact that roughly half the values fall well below that average. Similarly, assuming your earning potential stays fairly constant, is it realistic to budget based on a minimum value?

Using the parameters of these two distributions (and converting them to mean and standard deviation… which is beyond the scope of this article), we can actually find two means and two standard deviations for each peak in the data. From there, we can find the monthly income amount at a certain level of probability. Said another way, we can find the monthly income amount at which point 85% of the other values are above that amount… and 15% are below (the dipping into savings months).

So based on historical data and assuming our income stays within this distribution, we can set a budget amount that we have some confidence will fall short 15% of the time… or roughly two months every year. The other side of the coin is that 85% of the time we expect our monthly income to be at or above this level.

That budget level is about $3007 per month.

Armed with this amount, you can build a tactical reserve that’s designed to cope with the expectation that about 2 months a year your income won’t meet your budgeted needs. That tactical reserve could be:

- 2 months worth of expenses (in addition to your emergency fund!)

- The difference between your budget level and your minimum historical earnings (times 2); for example, the difference between our budget level and the minimum earned in the historical data is about $900. So having 2 x $900 ($1,800) may be a good tactical reserve.

Another angle.

What if you already have a set budget of $4,800 per month and are looking to make the leap into self-employment? You’re fairly confident that this income history is reprensentative of what you would earn… what does that probability look like? Since you’ve done the math, you find that about 45% of your expected monthly income falls at or below the $4,800 value.

It’s all about managing expectations. If you summed up the annual earnings from the first year, you’d find that you easily exceeded your annual budget. The second year, however, creates a net shortfall by $1,200. On balance, you’ve managed to create a surplus over the two years… assuming you’ve tactically handled your shortfalls and dealt with the fact that the second year had 8 months in which your income was below your budget. So there’s an argument for rolling over your tactical reserve into the next year… make hay while the sun shines, as they say.

The bottom line.

If you struggle with uncertain income and budget variance, then you’re probably not alone in the world of self-employment. If you want to get some help with smoothing out your income, please talk with us — the first consult is free and we’ll be able to explain how we can help you manage your cash flows, save for future goals, and keep your business and personal finances on track.

—

The information presented here is for informational purposes only. This document is not personalized investment advice or an offer to buy or sell securities. Targeted Wealth Solutions LLC does not provide tax or legal advice. Hyperlinks connect to other content that we believe to be from reliable sources. Targeted Wealth Solutions LLC is not responsible for the accuracy or content of outside information or links. The views expressed on external sites are not necessarily those of Targeted Wealth Solutions LLC.